On July 8, 1741 in the small town of Enfield, Connecticut, preacher Jonathan Edwards preached the sermon he is most remembered for today. It was also the message that would go on to change the course of American history.

Reading by candlelight off a manuscript in his usual dispassionate, monotone voice, Edwards was a far cry from the fiery preachers you and I have no trouble imagining. Yet the story goes that, while Edwards delivered his message to the congregation, people began to openly weep and mourn in response to his words. People interrupted Edwards mid-sermon with cries of “What must I do to be saved?” Some accounts depict congregants clinging to their pews for dear life for fear that the wrath of God be poured out on them at any moment. At one point, the cries became so great that Edwards was forced to discontinue the sermon altogether while pastors prayed with the people of the congregation. This sermon would light the fuse that would go on to become the First Great Awakening in America.

Today, we know Edwards’ sermon by its infamous and foreboding title: “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

Much of this, of course, offends our modern sensibilities. The idea that a group of people would respond to an unemotionally-delivered sermon with weeping and cries of sincere anguish is difficult to take seriously. Additionally, the spirit of Edwards’ sermon has been all but repudiated by the church today. There have even been efforts to directly oppose Edwards with on-the-nose titles like “Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God.”1 The juxtaposition of anger and love here is especially interesting to consider, as if love and anger are mutually exclusive to one another. Surely the God of Jonathan Edwards must delight in punishing the sinful, and we moderns are far too civilized to be bothered with the idea of an “angry God” anyway.

Despite his detractors, I firmly believe Jonathan Edwards understood something about the character of God that the Church has since lost sight of. His goal was not to manipulate his congregation to conversion through fearmongering and deception. Rather, his message was rooted in the knowledge of God and born of a rich and nuanced understanding of the Gospel. And I think it is time the Church reacquainted herself with the God that Jonathan Edwards knew.2

Misery Business

In a postmodern society developed beyond the perils of Edwards’ eighteenth-century New England, we no longer live in a world plagued by the threat of sickness and death. This is of course a good thing, but it is not without its side effects. While life was abjectly more difficult in Edwards’ time than for us, the people of Edwards’ day were keenly aware of their need for God due to their ever-present physical needs. Today, that need has been considerably lessened, due in part due to modern scientific advances; I’m very grateful to live in a world where I need not fear the bubonic plague. But the reality of this world has since produced a people who have little need for God when they have comparatively little essential needs at all. To paraphrase sociologist Philip Rieff, in Edwards' day people did not go to church to be made happy, but rather to have their misery explained to them.3 Today, people go to church to hear contemporary, catchy music, be entertained by a speaker, and hear something that makes them feel good about themselves. No one needs to have their misery explained to them in 2023, because there are so many better-sounding diagnoses and subsequent solutions out there than “your sin has separated you from Almighty God.”

This cultural shift in the way we understand church has had a profound impact on Christendom at large, in particular the way that Sunday worship is designed and delivered to the body by its leaders. When nonbelievers enter our doors on a Sunday morning, they are seeking a cure for a disease many do not know they have. There may be a vague notion of unrest or dissatisfaction in their soul, but that is likely the extent of it. They are then presented with a truncated view of the character of God, one that emphasizes his love for his people and ignores the majesty of his justice and holiness. This presents God as mostly like us, only kinder and more powerful. This God can help you become the best version of yourself, if you’ll only relent and open the door of your heart, where he’s been simply pleading with you to let him in. Given this limited depiction of the Gospel, it’s no surprise that the Church struggles to rally its members under one banner: it has unwittingly rallied its message and efforts around the individual rather than the Living God.

In order to understand what the Church has lost, and what she must do to recover it once more, we need to revisit what I believe was the driving value at the heart of Jonathan Edwards’ message: a faithful understanding of the fear of the Lord.

Know the Fear of the Lord

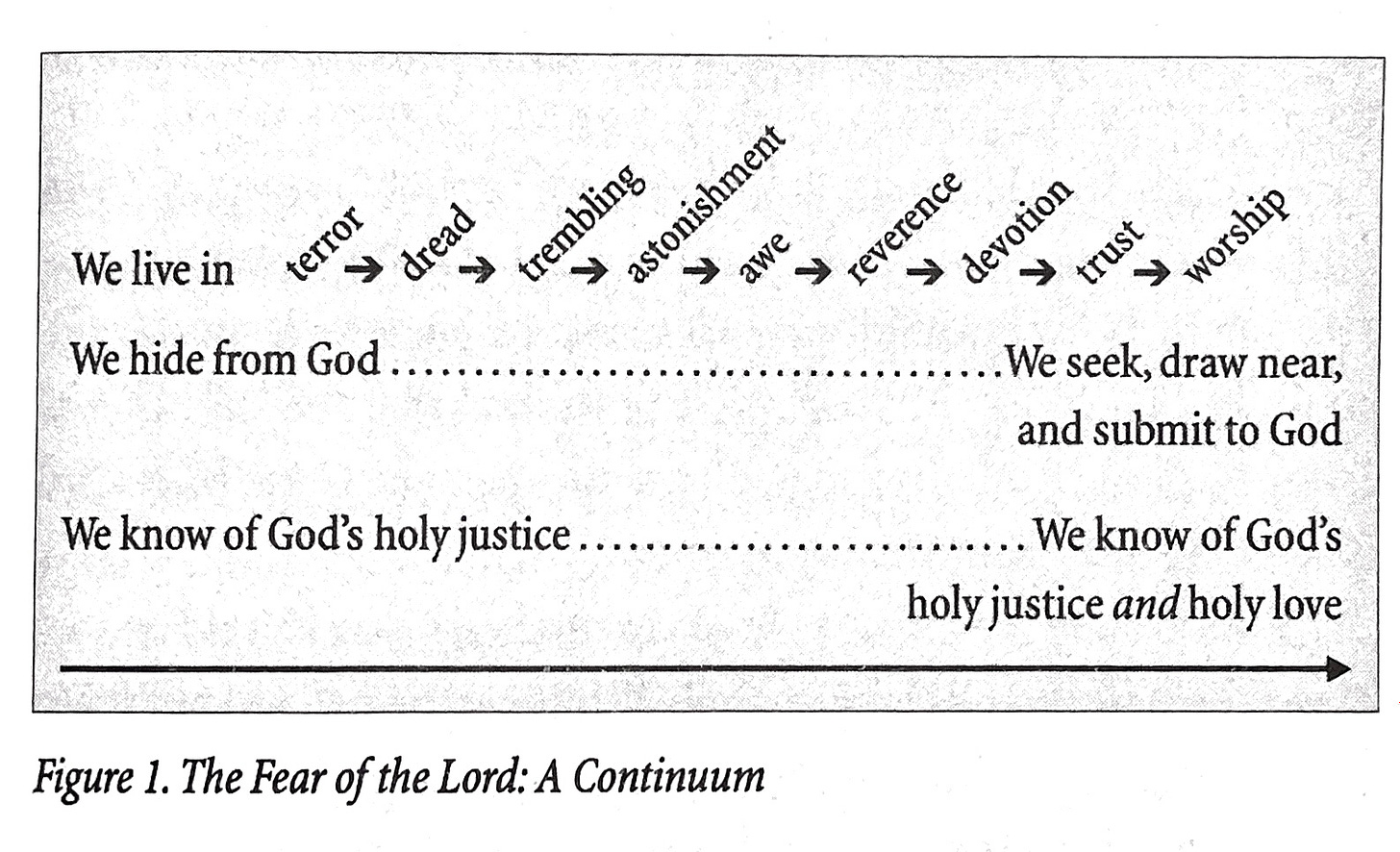

The title of this essay comes from a line from biblical counselor Ed Welch’s book When People Are Big and God Is Small. In it, Welch writes on overcoming peer pressure and the fear of man by understanding the fear of the Lord. In Chapter 6, Welch explains how the fear of the Lord is not merely the kind of fear that inspires terror, but rather exists on a continuum, offering the chart below to illustrate his point.

This chart is useful in several respects. First, it acknowledges that, to understand the fear of the Lord, we must acknowledge that there is in fact an appropriate role for “fear” in the classic sense of the word here. We see this demonstrated in the pages of Scripture, where those who have an encounter with God do everything from scream to render themselves prostrate to cover their face in horror. Modern Christianity has distanced itself from the idea that fear should play a role in the faith experience, yet time after time the Bible depicts fear as a catalyst for true heart change. It is not the only means of understanding the fear of the Lord, but it does belong on the spectrum.

Secondly, it locates and explains the reality of both the believer and nonbeliever with respect to their experience of God’s holiness. Read the chart from left to right. For the unbeliever, they are stuck on the left side of the chart, unable to move beyond their ever-present reality of dread due to not yet receiving the promises of God. For the believer, this fear ultimately fades out and produces “reverent submission that leads to obedience,” a holy fear charged with hope. Through the gifts of God’s Spirit, his Word and his Body, the believer comes to see God’s justice as running parallel to his love, as both aspects flow naturally from his holiness.

Welch then makes a stand against the love-anger bifurcation, stating that both are necessary aspects of God’s character:

“Notice especially the mighty acts of God that show both his holy love AND justice, kindness AND sternness. The psalmist reminds us that those who fear the Lord say, "His love endures forever" (Ps. 118:4), but they also say, "Who can stand before you when you are angry?" (Ps. 76:7). Scripture speaks of unimaginable love alongside holy anger…Therefore, we cannot rightly say "my God is not a God of judgment and anger; my God is a God of love." Such thinking makes it almost impossible to grow in the fear of the Lord. It suggests that sin only saddens God rather than offends him. Both justice and love are expressions of his holiness, and we must know both to learn the fear of the Lord. If we look only at God's love, we will not need him, and there will be no urgency in the message of the cross.”

Is this not exactly what we see in American church culture? In emphasizing the love of God over and against his justice and holiness, the Gospel essentially loses its critical spark and becomes diluted into little more than moralistic deism, a vague sense that we ought to behave a certain way because God says so, but it can be ignored or refuted whenever I so choose.

As a parent of young children, I understand this intuitively. I love my two daughters fiercely, but in our home, anger sometimes has a part to play, not as wanton and unbridled chaos but as the rule of law in the face of injustice. The writer of Proverbs echoes this when he says, “Folly is bound up in the heart of a child, but the rod of discipline drives it far from him” (Prov. 22:15). At times, my children require me to be something other than exclusively huggable. My girls will never truly love me if they do not also learn to revere my authority in our home.4 So it is with the fear of the Lord.

So we see that the fear of the Lord includes both a “terror-fear” and a “worship-fear,” and both are appropriate responses to a glorious and holy God. This is why the believer can say both “There is no fear in love” (1 John 4:18) and “‘Should you not fear me?’ declares the Lord” (Jeremiah 5:22). Both are true and can coexist, because for the Christian the fear of the Lord inspires awe and reverence, not simply terror. And it is only when considering the vastness of his holiness that we can come to appreciate the depths of his unfailing love.

Learning to Walk in Holy Fear

Our task then is clear: our every word and action as followers of Jesus must come drenched in the fear of the Lord. This is simple enough to state, but becomes much trickier when moving to application. Consider the far-reaching nature of the implications of this principle: cultivating the fear of the Lord in our daily life means praying and reading God’s Word every day, not out of a fear of punishment, but out of an appropriate fear of displeasing the Worthy One who has commanded us to do so. Living under the cross means forgiving one another in love, but walking in holy fear also means confessing our sins immediately in order to honor our King. Our worship services should be steeped in a reverence and awe for our Creator; we are not to mistake “come as you are” for “everyone gets an A, so don’t bother trying.” Our songs should roar of how great Thou art, not how great I am for singing them. And our sermons should be saturated with the weight of His glory, not the cleverness of our anecdotes.

I believe the American Church has become so preoccupied with getting people in the door that little else is often expected beyond that, be it discipleship, ministry or otherwise.5 The Body of Christ must seek a higher standard here if we hope to endure and pass on a legacy of faith to our children. If we do not revere our God with our words and actions, how will a nonbeliever see our witness as anything more than just one more behavior modification system among many? “When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you care for him?” (Ps. 8:3-4). When we know the fear of the Lord, the truth of the Gospel comes crashing into our daily routine and we come to see both both God and ourselves as we truly are: He is the Great Lion of Judah, and we are wretched sinners in need of redemption and a good Father.

“My flesh trembles in fear of you; I stand in awe of your laws” (Ps. 119:120). May the way we tremble before our God be the catalyst to an effective witness and a tether to our souls in every season of life. For the fear of man lays a snare, but whoever trusts in the Lord is safe (Prov. 29:25).

I am not in the habit of disparaging books I have not personally read, and since I have not read this I want to tread carefully here. Having said that, seeing as this book was previously listed on several Top 10 lists and has been widely praised by some well-known evangelicals, I thought it worth pointing out here given its relevance to the subject matter.

Note: If you haven’t read last week’s essay on the role of feelings and emotions in our walk with Christ, it functions as a Part 1 of sorts to this piece.

See Rieff, The Triumph of the Therapeutic, 1966; Pp. 23, 30.

To be abundantly clear, this is not the same as saying my children should be afraid their father will hit them or shame them in any way. I am not advocating for tyranny perpetrated in the name of love. Children can be made to acknowledge and come under authority in the home without being beaten or disparaged into doing so.

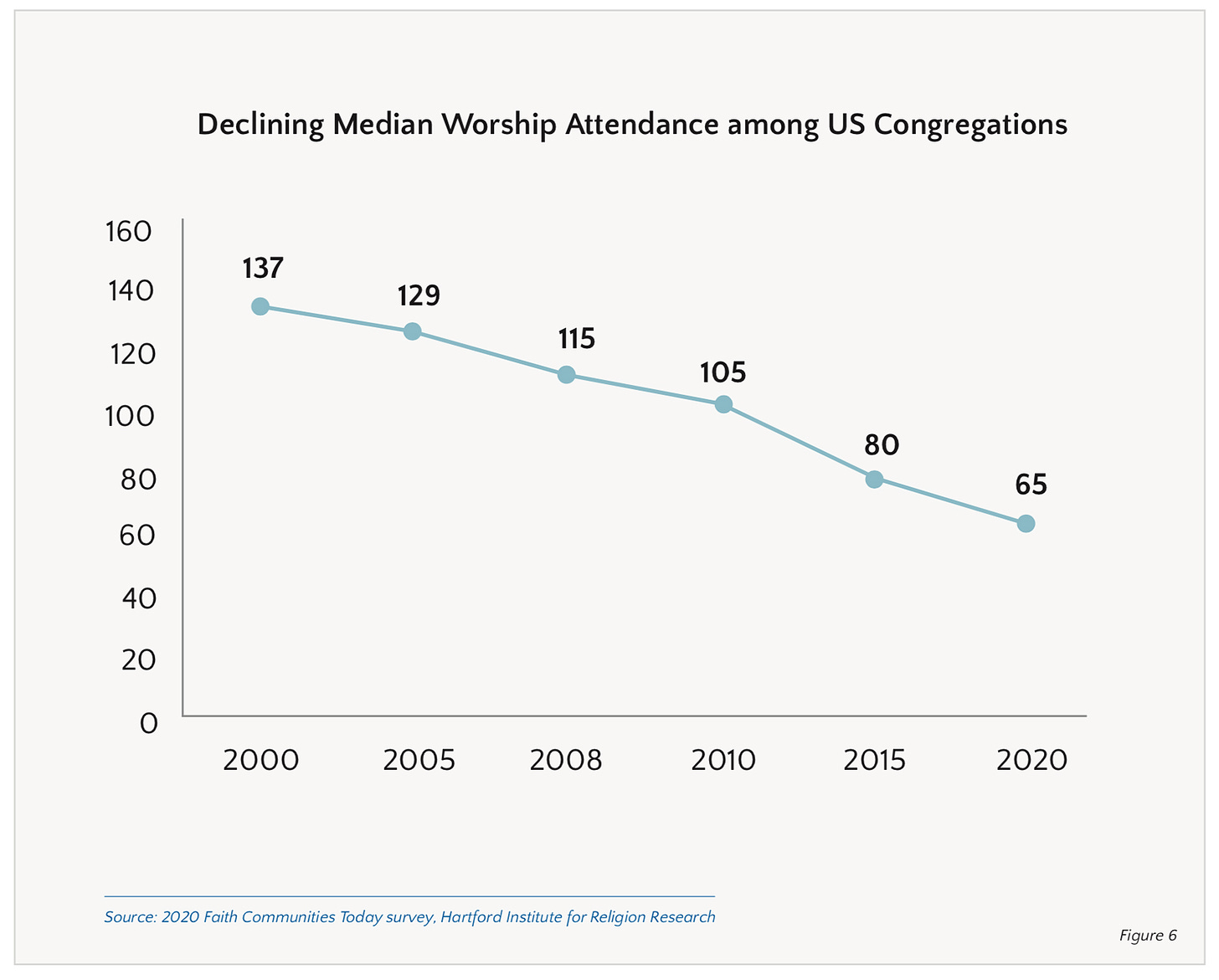

Not to mention that, in spite of every effort made to appeal to seekers, it’s not really working. I’m no statistician, but I’m pretty sure this graph is trending in the wrong direction:

Excellent read Dominick!! Reminded again of Gods faithfulness as I see the work He has done and continues to do in and thru you!