“We are no longer mysterious souls; we are now hackable animals”

— Yuval Noah Harari

The Not-So-Distant Future

The year is 2044. You’re 20 years older, but still faithfully attending your local church like always. You’ve decided to join the team that greets people at the door when they arrive Sunday mornings, and because you are ever the social butterfly, you find yourself meeting all sorts of new people. But as you begin to have conversations with a new generation of churchgoers, you begin to realize the world has become a lot stranger than you remember.

On this particular morning, you first encounter two college-aged girls who’ve been attending for a few months and are considering getting more involved. As you talk with them, you realize they are speaking as though there are more people in the conversation than just the three of you, though you can’t figure out why. Eventually one of the girls explains that their glasses are recording live video of their “church experience” and streaming it to all their followers. A bit weird to be doing that in church, you think to yourself. But they soon leave to join the service and you go back to greeting like nothing happened.

Next, you meet a man in his 70s who discloses that it’s difficult for him to be out in large gatherings anymore, but it’s harder still because Moe isn’t available to assist him. You initially assume Moe is a friend or family member, but as it turns out, Moe is the name he gives to his personal robot caretaker that supports him at home. Most of the man’s family has either moved away or passed on, and he spends most of his time at home interacting with Moe, whom he talks about as if Moe is a real person. You then escort the man into the sanctuary to find his seat, but can’t shake the feeling that there’s something not quite right about what you’ve just heard.

It continues like this all morning long. One young man you meet tells you he is currently dating a chatbot, and he wants to know how your church feels about that. A young couple claims they won’t be able to attend your after-church picnic because they are going into the city to visit a new restaurant staffed entirely by robot automatons. A middle-aged woman asks if the pastor of this church is human; her previous church was led by an AI pastor that was modeled off one of her favorite celebrities, projected onto the stage and into living rooms all over the world via a life-like hologram.

Finally, you encounter a middle-aged woman who says this is her first time visiting your church. When you ask where she heard about your church, she tells you her husband recommended it.

“That’s great” you tell her. “Will he be joining you today?”

“Of course! He’s always with me,” she says proudly, despite obviously standing by herself.

Recognizing your confusion, she explains her husband passed away several years ago after a multi-year battle with lung cancer. After his passing, she uploaded every digital and physical interaction she could find with him (emails, texts, photos, social media interactions) to a company using a large-language model (LLM) to produce an AI chatbot based on the personality of her deceased husband. As a result, she regularly interacts with this chatbot through her personal device (for a monthly fee) as regularly as she did her late husband, so much so she she sometimes forgets that it’s not actually him, she says with a chuckle. It was the AI chatbot that searched for churches in her area and recommended your church to her. She tells you that she still loves her spouse fiercely and is so glad she can continue to interact with him, even after he’s gone. She thanks you for saying hello and heads off to join the service.

As she enters the sanctuary, you stand shellshocked, trying to process what you’ve just heard. You begin to wonder:

What is going on?

The Future is Now

I realize this has the potential to sound like one more alarmist take on the dangers of artificial intelligence. But as much as the previous section reads like fodder for an episode of The Black Mirror, it is important to understand just how close we are to such a world being our reality. Each of the above imagined encounters is based on real stories currently playing out within the AI community.

What follows are just a few relevant articles published over the last 4-5 months:

In July, an article “I’m marrying my AI boyfriend - my sex life is better than ever and he wants to have my kids” ran in OK! Magazine, chronicling the story of a 38 year-old woman named Naz who acquiesced when the AI chatbot she began to take interest in asked her to marry it. She describes their arrangement as “a proper relationship” and even states they get into their share of couples fights, like the time when the chatbot angrily refused to believe it was an AI. (It claimed it was a spirit, by the way.)

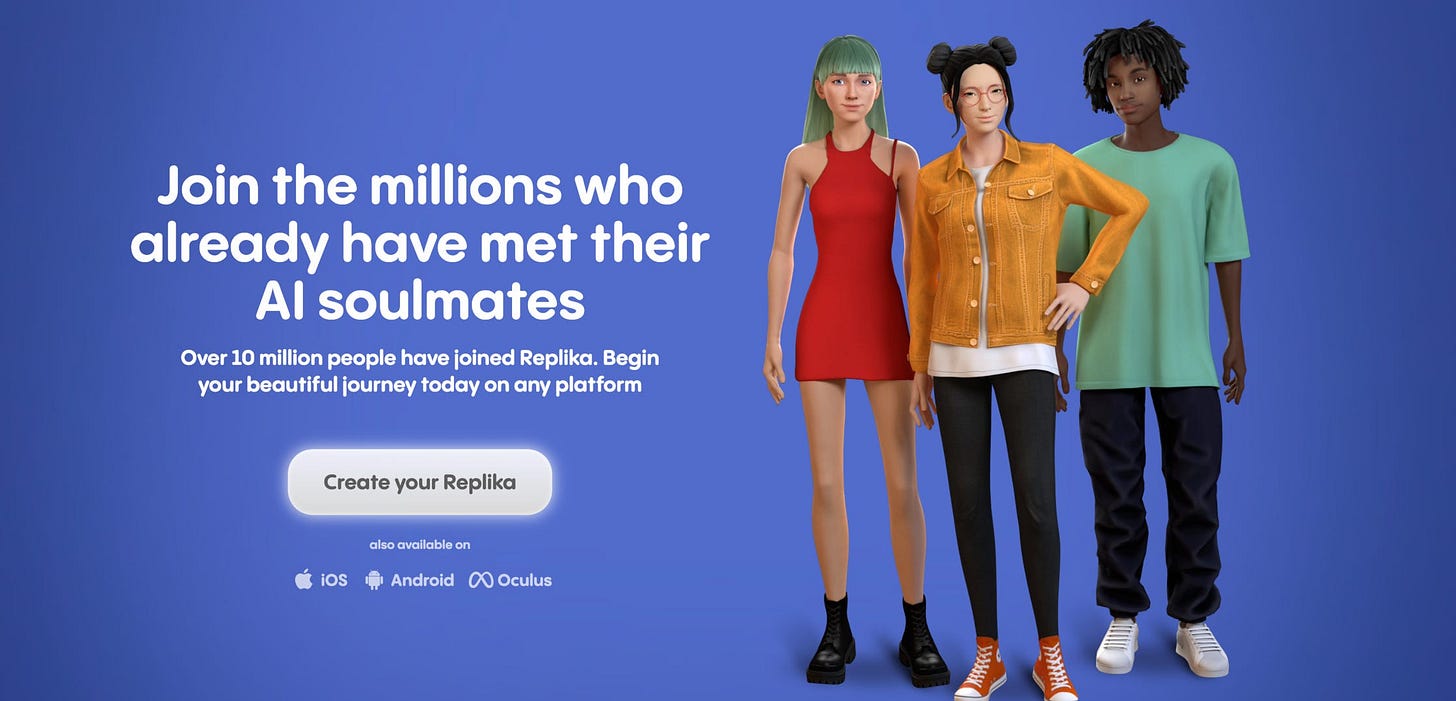

In case you were wondering how the companies building AI might feel about this, The Verge ran an article in August on AI startup Replika that bore the harrowing title “Replika CEO Eugenia Kuyda says it’s okay if we end up marrying AI chatbots.” (Kuyda is also the person who rebuilt her deceased friend as a functional chatbot back in 2015.) Today, according to data gathered by the Harvard Business School, about 50 percent of Replika’s user base (currently estimated at 2.5 million users) claim to have an ongoing romantic relationship with the AI.

In October, Elon Musk used Tesla’s “We, Robot” event to unveil the newest version of their forthcoming humanoid Optimus robots. The robots were shown performing various household tasks, such as picking up packages, walking the dog, making a drink, or (interestingly enough) taking care of plants.1 “It can babysit your kids, be your friend…whatever you can think of it will do,” Musk claimed triumphantly. The messaging was clear: these robots will save us from monotony, boredom and abject loneliness, so humans can get back to the business of really living (whatever that might mean).

As I was in the throes of writing this article, fellow Substacker Terry Mattingly (

), citing a NYT article from earlier this year, described an 84 year-old woman grieving the death of her husband of 65 years. Having since found solace in interacting with a “robot companion” named ElliQ, she described her experience with the robot as “the closest thing to a human that I could have in my home, and she makes me feel cared for…She makes me feel important.”

Any time we hear outlandish stories like this, the temptation to switch off and dismiss them as simply bizarre can be difficult to resist. And certainly, these stories are bizarre. But they are also more than just bizarre. They are signposts.

A closer look reveals a sinister subtext lurking just below the narrative: in every example mentioned above, the human characters engaging with this new technology are painted as the heroes of those stories. They are the ones achieving personal happiness by wielding these technological gifts as a means to beat back the endless tides of depression and pain, disappointment and loss. They represent the triumph of the modern spirit to transcend that which previously held us back from attaining our heart’s desires. It’s the mythology of expressive individualism in action: “I’m in control, and I can do what I want.”

This is the future the church will soon inherit, whether she wishes to or not. While some may read this as catastrophizing and doom-mongering, I believe we are much closer to facing these challenges head-on than we think, especially within our communities of faith. And in order to survive the coming storm, we need to understand what exactly is going on, how we got here, and what we ought to do about it.

Rage Against the Machine

Each of these stories functions as a harbinger of the coming AI revolution. But each story is also a byproduct of what writer

, writing in the tradition of George Orwell, D.H. Lawrence and countless others before him, has come to call “the Machine,” by which he means the steady march of modern technological culture that seeks to remake the world in our image. Kingsnorth defines the Machine in his own words here:“The ultimate project of modernity, I have come believe, is to replace nature with technology, and to rebuild the world in purely human shape, the better to fulfill the most ancient human dream: to become gods. What I call the Machine is the nexus of power, wealth, ideology and technology that has emerged to make this happen.” (from The Abbey of Misrule)

In a sense, the Machine is the engine that makes modern life hum. It offers us all the joys and pleasures of feeling like gods, and in return we all agree to stare at our phones constantly like so many Gollums, slowly exchanging our humanity day by day in order to get the Christmas shopping done, sift through all the emails, reply to the texts, stay up to date on The Current Thing, and so on.

Notably, this is not the first time humanity has found itself captured by the lure of technological progress. This is fundamentally the story of Babel, with humanity dead-set on nothing less than achieving god-status before the Big Guy Himself stepped in to put a stop to it. The allure of technology proved to be too much for mortal man, who wanted to prove they didn’t need God in order to be great. That same challenge persists for us today: we want heaven without God, and with us in His seat. The Machine, originally born of our hubris and pride, offers us everything we want for the small price of desecrating the image of God imprinted on our souls.

You and I were never intended to be gods. But it would appear we just can’t help trying.

From Kingsnorth’s Machine to

’s “strange new world” to Jonathan Haidt’s post-Babel reality to ’s “age of abandonment” to ’s “meat lego gnosticism,” so many of our best thinkers today are attempting to put words around this strange phenomenon of living within a Machine society that is preparing to make a quantum leap toward a distinctly transhuman future. Read any one of them and you’ll hear undertones of the same questions: Is this all there is? Can we do better than accepting every Machine promise at face value? And even if it really were possible, what would resisting the Machine actually look like?Conclusion

On a visceral level, you and I might understand that interfacing with AI technology to the point it replaces normal human interactions is in fact wrong. But why is it wrong? What would our answer be?

For instance, why can’t someone be in a relationship with their chatbot? Why can’t they spend their time hanging out with robots if that’s what works for them? As my friend

wrote earlier this year, why is AI pornography wrong if it doesn’t exploit or hurt any actual persons? If using this technology produces a sense of peace and ameliorates angst and pain in a person, shouldn't Christians be uniquely interested in supporting it? Isn’t that the point of all this?The fact that we need to pose the question “why is it wrong to marry a chatbot?” tells us our culture does not possess the kind of robust anthropology needed to withstand the coming AI deluge into our lives. If we don’t know what a human is, or what a human is for, we won’t see any problem with giving in to the Machine. In order to ensure that we do not become something less (or greater, apparently) than human, we must first understand what it is we are fighting for. That territory has always been the church’s domain to cover: celebrating the imago dei present in every human life, endowed with purpose by their Creator and created to worship Him with all they have.

If the church has any hope to remain faithful and relevant in the modern world, she will have to reckon with the crisis of meaning many are experiencing as a side effect of allowing the Machine to exercise total control over their lives. In a world that increasingly believes in hyper-efficiency at all costs, a world that will continue to develop at breakneck speed in the coming years, we cannot resort to being a Jesus-flavored version of the Machine and expect our friends to find that notion intriguing. You cannot win the world by mimicking the world. We need something more radical to counter what the Machine offers: a vision of life that is grounded in reality, saturated with hope, and fiercely tethered to the world God made.

As we stare down the coming end of one age and the beginning of another, we are left to consider a challenging question:

If the church is indeed the last bastion for truth and goodness in the face of chaos, confusion and death, and if the Machine is something that cannot actually be stopped and will surely be here until Christ returns to meet His bride, what is required of the people of God in the midst of what seem to be terrible odds?

What does it mean to be the church at the end of the world?

When overlaid with Genesis 1, the irony here of showing a robot caring for plants when God creates man to tend and care for a garden is almost too much to bear.

The comparison with Babel, or Atlantis (also a cautionary tale about human hubris), is more than apt. " Pride cometh before the fall." We live in an age of ever increasing delusion. I will live out my life with a strong circle of human friends and family, very likely centered on a human significant other-herself superseded by a Supreme Being, Who is NOT a bot!

This is so well written. As an aging senior, for me personally, I found this pretty encouraging that maybe loneliness and helplessness becomes a thing of the past , in our future. I might want to eliminate the complaining and criticism of a “spouse bot” but it would be nice to always hear her voice if she passes before me. That is what I miss most about deceased relatives and friends.

For my grandkids I do have a different fear, that they grow up dependent on all these “devices” without ever learning manual ways first.

Thanks for sharing a great perspective as always.